“Credit Where It’s Due, But That Was There When We Arrived!” by Morocco (C. Varga Dinicu) © 2017

Almost from the moment Roma arrived in Europe, the Gaje’s racism and fear of the “unknown” caused them to blame Roma for miscellaneous “crimes” they did not commit, unwillingness to work or settle down and creating conditions of squalor where they did stop that was not only not of Roma making but often deliberately created “fake news” — to divert blame from themselves onto their victims.

In fact, there were numerous laws in several countries prohibiting Gaje from employing Roma in most professions, selling or renting property to them and/or requiring Roma to be gone from the village, town or city by sundown. Of course that led to repercussions: beatings, killings, jailings, actual enslavement and other punishments and long-standing negative assumptions that persist to this day.

Ironically, Roma are also “credited” for inventing or introducing “safe”, mostly entertainment forms of ethnic music and dance — often the only professions allowed to them — which were already there and a part of the local cultures before Roma even set foot in those pertinent countries.

This paper will touch on three of those ethnic dance forms and is based on reading, observation, questioning of Roma and “ethnic” performers of said dances and music and extensive in-person participation/ learning by assimilation in:

- Zambra Mora — originally from Morocco, brought to Moorish-ruled Andalucia and from there to the rest of Spain, but now considered just a palo and not a form of Flamenco dance;

- Ghawazi — once prevalent in many styles/ variations, according to which dancers were most popular in a given town. The little that is left is found in Upper Egypt; and

- Roman (Sulukule) Karsilama, a newer, popular “bluesy” 9/8 used by some Turkish dancers in their Oryantal routines and done for fun by all at family and holiday celebrations, the music for which is most probably “borrowed” from Armenian Tamzara, a line and circle folk dance.

All three are erroneously assumed by most Gaje to be of Roma origin or invention.

Zambra Mora

To this day, Spain is reluctant to acknowledge its huge cultural debt to the Moors, but the evidence keeps turning up everywhere. Zambra Mora means Moorish Party. Mora = Moorish/ North African (Moroccan, Tunisian, Algerian) in Spanish. Zambra is Maghrebi for party (hafla, glendi, kef, maharagan or farah in other areas). Zambra can also mean the party’s location, a show or band of musicians. In Granada, it means dance shows performed by Gitanos in the Sacromonte Caves (also called jaleos) and zambra also means moorish boat!

Ana Ruiz researched in current-day Spain and erroneously concludes: “Zambra Mora never was a dance, but a form of Flamenco song and guitar with the heaviest Middle Eastern influence of all the palos or styles of Flamenco music.”

It definitely was a dance. I learned Zambra Mora in the mid 1950s from Carmencita Lopez, my Spanish-born and raised Flamenco teacher — as did the students of all other New York Flamenco teachers, who had also learned it themselves in Spain. There were a few different styles of Zambra being taught and performed, depending on each’s particular region and subsequent development therein, since there were no computers, YouTube, and instant proliferation/ copying, like we have today, to homogenize them.

I danced a Zambra Mora in 1958 at a Persian Norooz party at the Waldorf Astoria — before I ever saw or knew what Oriental dance was. They loved it. I was accompanied by my then guitarist, Diego Castellon, brother of Sabicas (1912-1990). Both gitanos told me about women who danced it, crediting many of their own beautiful Zambra Mora melodies to their father and grandfather, also famous guitarists in their era and to Carmen Amaya’s father, “El Chino”, who also played Zambra Mora. I’d seen many bailaoras, including the gorgeous La Chunga, do it — barefoot, as was her general style, but not with finger cymbals. Others used them in Zambra Mora and Carmencita, herself, taught it using chinchines.

The most likely reason Ana found music but not the dance is that it went out of fashion over 45 years ago — audiences preferred dances with more energy and taconeo. Flamenco has changed a lot since I studied and performed it, over six decades ago — for instance, adding a cajon, unheard of back then!

In Washington Irving’s book “Tales of the Alhambra”, published in 1832, he recounts several legends about the times of the Moors, related to him by caretakers and inhabitants of the Alhambra, when he was the U.S. ambassador to Spain and actually lived in the Alhambra. He was also an avid historian, including some history of Moorish times in his book.

When he writes of the dances women and men did while he was there, he calls them Fandangos, as the locals did. When he writes of the Moorish times, the women are often described as dancing Zambras, which is what the local storytellers called them.

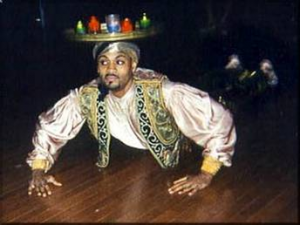

When properly done, Zambra Mora has sinuous hands and arms — softer than the usual brazeo flamenco — much floreando (hand and wrist movements) or with finger cymbals (chinchines in Spanish) throughout. Not only is there no taconeo (footwork), it can be done barefoot. There is no fast hipwork, but a lot of curved hip moves and an occasional hip-drop, bedlah-like costume: blouse tied under the bust, skirt tight around the waist and hips, very flared, long, with a bottom volante (ruffle) and many underskirts or petticoats. If a dress is worn, it’s very fitted in the torso, with the flared part sewn on at the hipline seam.

The word Flamenco comes from Arabic, though Iberophiles insist it means only “flamingo” or “Flemish”. It does, also, and I could explain why those “translations” don’t compute, but it doesn’t belong here. If some try to deny it, that doesn’t make it untrue, especially when deniers are the sort who spent over 500 years trying to stamp out Flamenco (sorry!).

They’d rather believe the taconeo (footwork) of Flamenco came from Kathak dance, via the Roma, than from Morocco and the Moors, so that is the story they tell. Yes, Kathak dance has a lot of footwork and so do tap, Irish step dance, clogging, Schuhplattler, etc. Many peoples have dances with rhythmic footwork but the technique and style of the footwork in Kathak is so different from Flamenco, that it is as incorrect to say taconeo came from Kathak as from Schuhplattler or Coeli. Flamenco was already omnipresent in Spain long before the Roma got there.

From Ana Ruiz‘ 2008 book (with her kind permission) “Vibrant Andalusia” (slightly edited): “Originally this Arabic term (Zambra Mora) was used to describe noises made by lively crowds and certain musical instruments, such as in a party or celebration. The term was applied during the 15th century in Spain when the Moriscos (Muslims and Jews forcibly converted to Christianity) continuted their famous traditional Moorish celebrations of song, dance, music, comedy and story telling or ‘Zamr.’ Documents from the 1600s describe Zambra Mora as festivities with music of instruments such as pipes and flutes. Zambras or Moorish parties became famous within Christian courts during the 16th to 18th centuries.

Zambra also meant a band of musicians and may have derived from the Arabic word samra, meaning an evening party that went on all night or zamara, meaning musicians. The word was also used to describe an uproar or sound of eastern instruments and muffled voices with merry-making.

Gypsies migrated to Spain about the same time that Muslims and Jews who did not convert to Christianity were being persecuted and expelled. They easily assimilated the Arabic or Oriental styles of music and dance. Remember that the Moors had occupied Spain for nearly eight centuries. Here are the origins of Flamenco. From the Zambras of the Moriscos we get the custom of shouting ‘ole’ which is derived from the Arabic expression wa’Allah (by God, or by Allah)

Those Gypsies and Moors who could not afford to relocate and remained in Spain after the Christian conquest, began to blend among each other as their skin tones were somewhat similar. The Zambras of the Moriscos continued to be performed and eventually integrated or evolved into the popular Zambras of the Spanish Gypsies of Granada during the 19th century, known as Zambra Gitana (Gypsy Zambra) that replaced the Medieval Zambra Mora.

After the Reconquest, celebrations of the Gypsies of Granada were known as Zambras and still are. There are few records of how they danced at the Zambras of the Moriscos (as with all dances of common folk).

The Zambra Mora was banned at various points between the 16th and 18th centuries by the Catholic Church as all things Moorish (ie. language, clothing, religion, festivals, dance, bath houses, mosques, and Arabic musical instruments), were all prohibited. However the Zambra Mora did eventually persist as long as it was an actual Christian festival with hired Moorish musicians, dancers, and entertainers, as opposed to being a Moorish festival honoring Allah as had occurred in the past.

We now realize how much racism and fantasy informed the inaccuracies of most Orientalists. It’s the same with Flamenco: only after people like Carmen Amaya, Antonio, Jose Greco, Pilar Lopez, Ximenez and Vargas (in whose Ballet Espanol I danced over 50 years ago!) and more than all the above, via his rave reviews at the World’s Fair in NYC in 1964 and some award-winning films, Antonio Gades, after Flamenco had become loved and respected in the rest of the world and a big money-making tourist attraction back home, that it began to be accepted and respected in Spain. Prior to that, it was considered something only the lowest classes and gitanos did for fun and profit.

A student writes: “My teacher says Zambra Mora is a myth, that a dancer in a movie did it, so people think it really existed”.

Flamenco today is very different than it was 50 years ago — much has been lost, changed or fused. I had the advantage of working and studying with (among others) first cousins of Carmen Amaya, Olga and Curro Amaya, when they were all still dancing: lots closer to the source then, than what is available today. I did Zambra Mora in 1958. I have several Flamenco records from the 1950s with Zambra Mora pieces on them. Were all those musicians and dancers lying to themselves?

There is another dance that’s simply called Zambra, which has taconeo and can be done with castanets, different from Zambra Mora, though both are Moorish in origin.

Ghawazi

Public performers were those who performed outdoors, in official, specific squares or in tents and on stages at moulids and other official holidays, when entertainment was usual, rather than at private events in homes or in theaters. They didn’t just get up and dance randomly on public streets — that’s another widespread Western fantasy. Not all public performers were Ghawazi. (None of them were Awalem)

The Arabic noun, ghazi, means invader or warrior. It’s also a male first name. The verb means “to conquer, raid, invade.” Sinti men used to be paid mercenaries, hired to fight others’ battles. They actually were warriors and invaders! They settled where they could, gave up being warriors and some men became musicians, horse traders, etc. Yusuf Maazin told me his grandfather brought the extended family to Egypt from Fars (Persia/ Iran), but that earlier Maazins had also spent generations in Syria/ Lebanon.

The feminine, ghaziyya means “female warrior/ invader” or “wife/ woman of the warrior/ invader”. Over time, usage of the feminine form changed, due to their much more publicly known (and now much less violent) profession. Most probably, this is where the interpretation or designation “Invaders of the Heart” comes from. Meanings of words often change over time — like what sly and pretty meant in Shakespeare’s time and what they mean today. In some modern, colloquial dictionaries, the female form of the noun, ghaziyya, is now defined as “woman dancer, danseuse.”

In “The Romany Trail: Gypsy Music In Africa”, a film by Jeremy Marre from the early 1980’s, there is an interview with one of the Banat Maazin. They translated what she said as: “They call us Ghaziyya. To them it’s an insult. To us, it means we invade their hearts with our dancing.”

The Ghawazi are Sinti, were from another part of India and arrived in Europe separately from the Roma, but the locals lump them together, so Marre’s documentary did too. All real Ghawazi are Sinti, but not all Sinti are Ghawazi

Ghawazi musicians and dancers used to be a very important part of every Egyptian festive occasion — weddings, engagement and circumcision parties, moulids. Different regions in Egypt had different Ghawazi families doing different dances to local popular music: Luxor/ Karnak /Quena region and Sumbat are two examples, and two different styles. Often, local women would hire female musicians and entertainers and men partying with the men would hire male professional musicians and female entertainers.

Though impacted by more modern big city music, male musicians still find work, female Ghawazi dancers are starving because of the changing religious and social climate.

The Ghawazi in Sumbat have not danced for over 40 years. A documentary film company came and paid them to perform. Their neighbors felt the dancing damaged Sumbat’s reputation, so they pressured the Sumbati Ghawazi to totally stop dancing.

Ghawazi dance and costume are not what’s expected anywhere for night club, restaurant or wedding shows. Costumes depended on what was in style and available. What some Westerners assume to be old-style Ghawazi costuming, based on Roberts’ and Gerome’s 19th Century paintings, was what upper-middle class Ottoman women wore at home but covered up on the street. Dancers did the same movements and wore the same clothing, with scarves around their hips (to better show their movements), using the best fabrics possible to show their wealth and status, but this was still everyday clothing.

The Maazin sisters told me that they created and made their elaborate costume as a way of declaring their uniqueness — pure show biz. There was a real resemblance of the Banat Maazin’s much more elaborate costumes to much earlier styles, as seen in 1893 World’s Fair photos. They stopped making and wearing them in the late 1980s, switching to fringed thobe beledi which were quicker, cheaper and easier to make and lighter to wear and carry.

Ghawazi had different origins and customs from the locals and were considered disreputable because the women were out in public, earning most of the family’s money. They sang, danced and drank tea or coffee and talked to men they weren’t married to. The culture’s view was that all women who performed or conversed with non-mahram men might be available for other services, when Ghawazi usually were not.

Ghawazi were more respected by their public than Oriental dancers, but not by much. Prejudice against Ghawazi continues to this day. In the 1980s, when I helped Abdelrahman es Shaffei bring over and advertise his Firqua Masr el Samer, a real folk group, which then included Metkal Kenawi and the Musicians of the Nile, the Egyptian and American governments would not give exit visas to the real Ghawazi, so they could perform with their own musicians. They sent somebody from the Kawmiyya instead — who was uneducated in this area of dance. It didn’t matter to those bureaucrats.

Early versions of raqs beladi and sharqi existed in North Africa and the Near and Middle East well before anything vaguely resembling a Rom or Sinto arrived. The dances the Ghawazi do were picked up en route. There has never been a famous Oriental dancer in Egypt who was a Ghaziyeh because Raqs Sharqi was taboo to them.

Roman (Sulukule) Karsilama

Because music, singing and dance were one of the very few areas of work allowed Roma, the talent, skill, and creativity that those Roma musicians, singers and dancers brought often took an existing form to much higher expressive levels, technique, and creativity, which accounted for the popularity of using this otherwise disrespected population in the arena of entertainment. In fact, Gaje assumed and expected that every Rom or Romni could do all the above.

Roma simply play whatever music is there, do whatever dances are local, but aren’t afraid to improvise and put in “soul”. Django Rheinhardt (who was Manoush) played fabulous Jazz. Hungarian Gypsies play Csardas — that’s Hungarian. Romanian Gypsies play Doinas and Horas — those are Romanian. Greek Gypsies play Kalamatianos, Tsamikos, whatever Greek music they learned. Turkish Gypsies play Turkish music — but they did come up with the Sulukule/ Roman variation on the 9/8 and a lot of Roma women do Oryantal in Turkey, so it would be fair and correct to say that Turkish Roma musicians and dancers had an influence on modern Turkish Oriental dance, but it was already in Turkey when they got there. They didn’t invent it or bring it with them from India.

Real Karsilama is one of the Turkish 9/8 line and circle group dances. However, at family celebrations, attendees might also dance to the more lively version of that rhythm using Oryantal movements. Semra, a well-known Turkish Oryantal dancer in the ’50s and ’60s, ended her routines dancing to an upbeat Karsilama, to distinguish herself from the dancers from Arabic-speaking countries, who used less syncopated rhythms for their finales. It was successful, so it was imitated — mostly in Turkish and Greek venues.

About 20 years ago, a dancer decided to use “Mastika”, a popular song with a “heavier”, more dramatic, accented 9/8 — exactly like the rhythm and style played for an Armenian Tamzara — and also mimed washing laundry in her Oryantal performance. It was an inside joke, because young Roma daughters-in-law spend most of the early years of their marriages doing the family laundry. Again, it was successful, so it was imitated and in this case, it’s 50/50: a Romni did “invent” the style, but the attitude and music were already there in Turkey.

A dancer posted: “Kathak dance, an ancient dance form in its own right, blends classical Persian head and arm movements with Rajasthani folk steps that Pakistan Roma do. The footwork is reminiscent of Flamenco”.

Roma didn’t invent Kathak, one of the many classical Indian dance forms done by many non-Roma Indians too. Roma also did Barata Natyam, Kuchipudi, Manipuri, Odissa, etc. styles. Now those still in India and Pakistan do Filmi dance as well. The closest thing to a specifically Rom dance form in India is Rajastani dance — very different from Kathak.

There is also audible, rhythmic footwork in Russian and Ukrainian dance. It does not make it automatically related to Kathak or any/ all other dances with footwork. Kathak footwork is very different from Flamenco. I know: I’ve done them both and can show the great differences. The Houara of the Middle Atlas of Morocco is where the basics of Flamenco footwork and turns come from and there were never any Roma there!

While it’s obvious that being unjustly blamed for negative or criminal acts and attitudes does nobody good – especially the accused, ironically neither does being incorrectly “credited” with inventing something. Get the facts and give the credit (or blame) where due.

(Presented on April 29, 2017 at Sare Patria: Romani Action as part of the Opre Khetanes V Festival and Conference on Romani [Gypsy] Musics and Cultures arranged by the New York University Department of Music in New York City)